Two really fabulous books have arrived in the mail over the last few months. One I bought and one was a freebie, given that some of my design work appears in it. (Whether the latter revelation invalidates me as a reviewer, I’ll leave you to decide (after explaining that it’s probably within my nature to be more critical, rather than less, of anything in which I’m included, though I guess you’ll have to be the judge of that as well)).

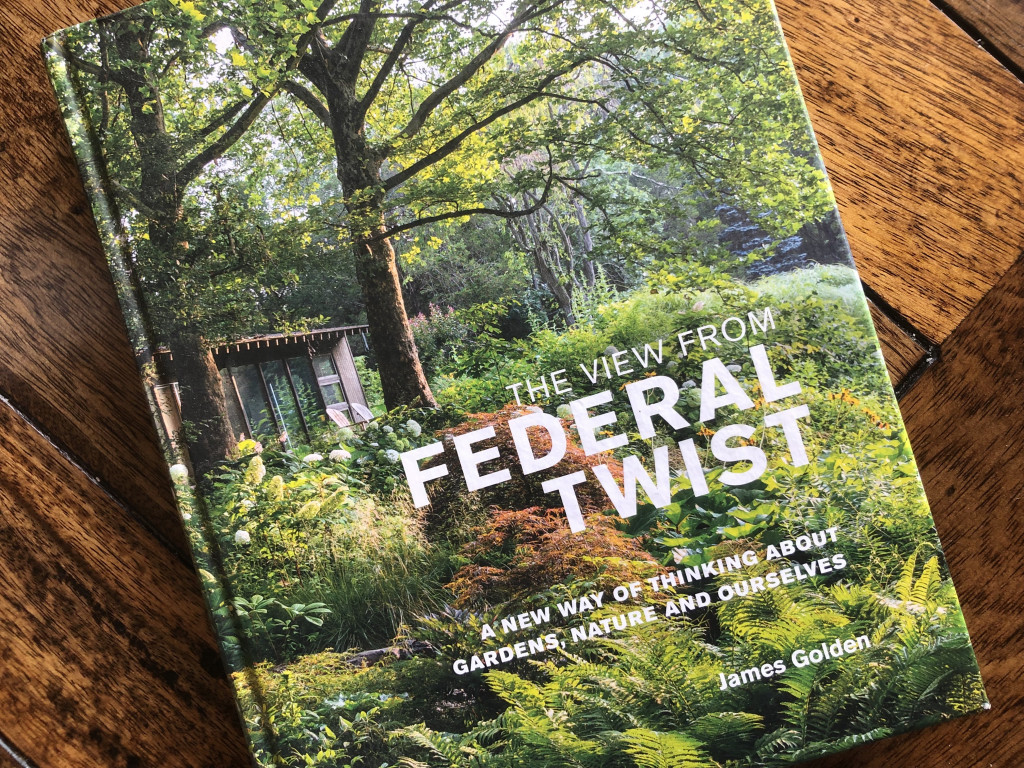

The first is James Golden’s The View from Federal Twist (Filbert Press, 2021)

Expectations were high with this one. Firstly, I really enjoy James Golden’s writing and his line of enquiry. Secondly, I love the curious setting of this garden – a glade in deciduous woodland. And thirdly, I expect a lot of anything that Filbert Press chooses to publish (having published titles by Nigel Dunnett, Dan Pearson and Olivier Filippi, among others).

It delivers on all fronts.

There’s something particularly powerful when a writer from one field crosses over to another. And in this case, writer James Golden has found himself, in retirement, stewing over gardens and gardening, and writing about it. In doing so, he sees through a slightly different lens, and we get to put on his glasses, inevitably recalibrating our own field of view and focal length along the way.

This is a gift to gardeners like me who, thinking over this stuff ad infinitum, can’t help but establish the Edward De Bono-described thought-topography, in which any new idea or consideration falls, like rain, onto my neuronal-landscape, and is funnelled down well worn pathways, or gets dammed up in lakes and ponds from which it can’t move.

Following someone else’s well-articulated thought-stream is a great way of redirecting or undamming your own.

Add to that the fact that Golden is not writing as an expert. He’s writing as a gardener on a steep learning curve – my favourite kind of writing.

Then there’s the garden itself, which has been created in (from what appears to me from the hundreds of pics I’ve seen), a beautifully proportioned clearing in deciduous woodland in New Jersey, USA. The quality of such a space is always going to be judged (mostly subconsciously) on the proportion of the lateral dimensions to the height of the trees, and while there’s probably no perfect equation in there, we know instinctively if a space is so small that it feels claustrophobic, or so large that it lacks any sense of intimacy or recognition of human scale. The site of James’ garden seems to be just right.

Then there’s the fact that deciduous woodland is novel and endlessly fascinating to we Aussies, given that we have nothing like it here.

But that, despite the novelty value of the setting, leads me to the greatest benefit of this book to Australian gardeners – that being James’ experimentation with planting straight into the existing vegetation, having ascertained that any attempt to get rid of it and start with a clean slate would be futile. This is a whole new way of thinking. But as this experiment makes clear, breaking new ground in this direction is going to take a LOT of thinking, and while it may end up providing some very cost-effective and low-interventionist ways to go about making a garden, the pathway through to such simplicity isn’t going to be easy.

In this approach there’s a similarity to the work of Kurt Wilkinson, in South Australia. The setting and the situation couldn’t be more different, James Golden’s being permanently sodden, and Kurts being mostly dry, but both are playing with ideas of how to overlay a sense of visual organisation to a setting with a minimal amount of intervention and resource.

The only thing that Aussie readers might find slightly disconcerting is that James is clearly one of those characters who quickly finds the best information and the richest thinking in any area he’s interested in, but then uses the jargon of that world (in this case the jargon of naturalistic planting design) as if it’s universally agreed and widely familiar. This can leave the reader feeling a bit like an outsider. But I never felt like I couldn’t determine, from the context, his meaning.

While none of the specific planting information in this book may be directly relevant, given the climatic differences with anything here in Australia, there’s so much that can be extrapolated from it.

And if you’re in any way stuck in a rut, it’ll help lever you out.

Then came Wild (Phaidon Press Limited 2022)

This is a book I’ve been waiting years for – an worldwide overview of naturalistic planting; where it started, where it’s at, and where it’s headed.

Rarely could you say about a book like this that it was both written by, and photographed by, the best people in the world for the task. When it comes to the writing, you could go so far as to say that no one else but Noel Kingsbury could have tackled the job. He has spent most of his career looking at, experimenting with, teasing out, thinking through and writing about naturalistic planting. Noel was, for decades, Piet Oudolf’s ‘voice’ in written English, having authored many books with him. And since the very first book of his that I ever acquired, in 1996, it has been clear that his and my brains work similarly, and the stuff he tells me is exactly the stuff I feel like I need to know – as if he’s writing in response to my direct questions. Lightbulbs are forever coming on in my head.

This is certainly the case with ‘Wild’. And I love that while the main text is rich in such revelations, I even find that apparently throw-away observations in captions contain knee-slapping moments for me, so that I’m forever thinking either ‘Gosh – I’ve never thought of that like that before’ or ‘Dang, I wish I’d written that’, or ‘Now that – that has never been said, or could never be said, better!’.

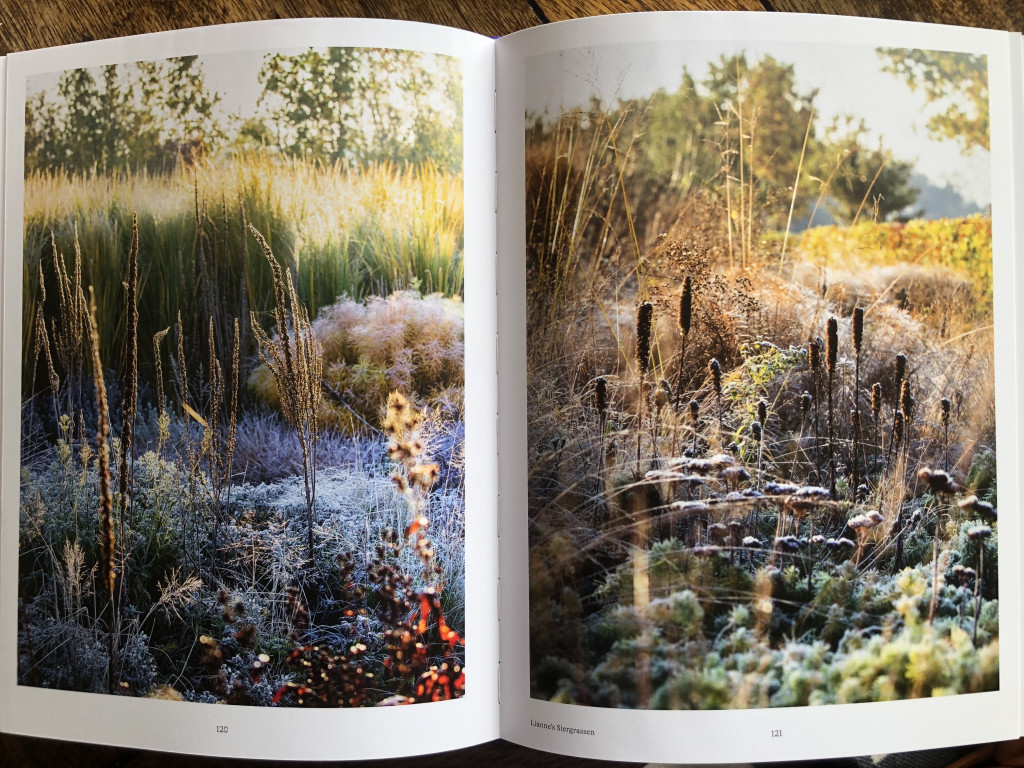

And then, of course, there’s Claire Takacs sensational photography. You could argue that naturalistic planting is more dependant upon perfect and magical light than any other form of planting. Or maybe it’s more that naturalistic planting is more transformed by perfect lighting than any other form of planting. But in either case, as a harvester or capturer of light, Claire Takacs is a genius.

None of that is to say that this is a perfect book.

To keep it quick, here’s a few points of minor irritation:

The design of the book takes some getting used to. The heading to a full page of text on any particular garden is in the centre of the page in which the text is divided into three columns, so I kept making the mistake of starting my reading at the heading, then having to return to the top left once I got to the end to fill in with the rest.

The design also means that many pics are reproduced at such a diminutive scale that you feel like getting a magnifying glass in order to get a better grip. And the size doesn’t reflect the scale of the view. You’d expect that the large-scale views would be reproduced large, and the smaller pics would focus on planting cameos, but this isn’t the case.

Finally, and most disappointingly, the photographic reproduction isn’t perfect. It’s hard to tell if the problem is the gloss level of the paper, or some other aspect of the production, but Claire’s pics don’t ‘sing’ in quite the same way they do in her two Australian productions – Dreamscapes and Australian Dreamscapes. They’re good. They’re really good. But knowing these other productions, you can’t help but be aware of the lost opportunity.

Having said that, these faults all leave you with a sense that the publisher was trying to pack an enormous amount of information and imagery into this book – arguably too much – but that you’d rather that they erred with this kind of generosity than to have made the opposite mistake. And they get lots of compensatory points from me for that cover, alone.

This is an important book. And it’s a fabulous book. You need it.

Would love to hear your comments if you’ve read either of these. Or any other recent arrivals we should be aware of…